CONTENT WARNING for discussion of sexism. SPOILERS for Only Yesterday and The Tale of Princess Kaguya.

Womanhood is fraught under the patriarchal umbrella. This motif prevails in the animated realms of the late Takahata Isao’s women-centric Studio Ghibli anime masterpieces. His 1991 drama Only Yesterday and 2013 swan song The Tale of Princess Kaguya both feature heroines at the whims of a man’s world.

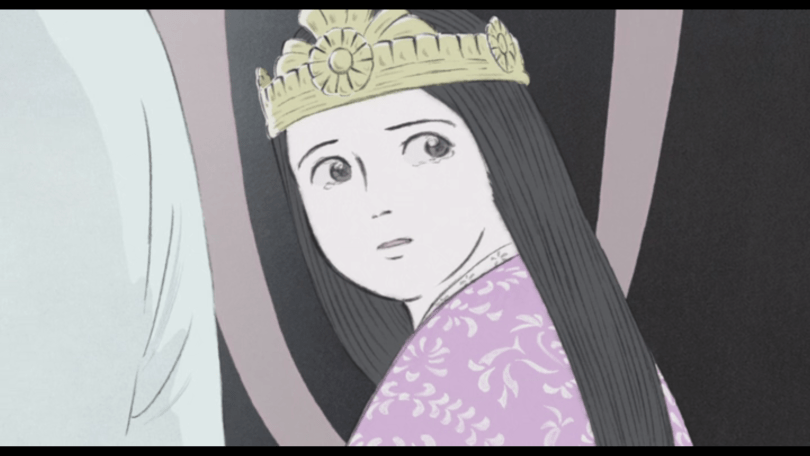

Only Yesterday follows the memories of office woman Taeko Okajima as she reflects on the mishaps of her younger 10-year-old self, her childhood resurfacing in a succession of unthreaded flashbacks. Based on a famous 10th-century Japanese folktale, Princess Kaguya flows through a linear coming-of-age tale, where its protagonist matures exponentially from infanthood to a tragically short teenagehood as she’s forced to grow up too fast. Through these narratives, Takahata interrogates the patriarchal entitlements that strangle Taeko’s and Kaguya’s expression of girl- and womanhood.

The fathers of Taeko and Kaguya are forces that can give or take in their respective family units. When they give, they’re a source of comfort and guidance, such as when Taeko’s father gives her a gentle reproach on her materialism when she begs for a purse. For all her father’s exterior sternness, Taeko’s sister mentions that he spoils Taeko with gifts.

For Kaguya, it’s established from her infanthood that she’d rather crawl to her father than to the chanting neighbor boys. Though bumbling, Kaguya’s father has the best of intentions. When he discovers gold and kimono silks in the bamboos, he imposes on Kaguya the lavish lifestyle she deserves—or so he assumes. In his eyes, he’s doing what’s best as a provider for his girl, the same way Taeko’s father is a breadwinner for his family.

But even though their fathers may be giving figures, Kaguya and Taeko also feel the constriction of their fathers’ standards. Giving is not so much a benevolent care-taking action as it is an unwitting exercise of power over their daughters.

Though her father may give her advice, young Taeko finds little room to negotiate with his strictness when he denies her a purse. Likewise, Kaguya’s father provides her new kimonos, but they come with restrictions, as her father expects her to walk and talk like a princess in her regal clothes. Although the fathers may offer warmth, lavish possessions, and good intent, their giving comes with conditions, in that if the fathers are (assumedly) in charge of their daughters’ needs then they can override their daughters’ own pursuit of their wants.

Fathers can be takers of dreams, too. The two girls navigate their desired goals under patriarchal rules, often within the pretense of their fathers’ narrow ideas of “I know what’s best for my girl.”

Kaguya knows that she pines for the fields more than a palace life, but she eventually succumbs to propriety in order to not upset her father. She may rebel against her princess education, but she never asks her father to cancel her lessons.

As her instructor reprimands her, “Do you really want to hurt your father?”, it’s implied that Kaguya doesn’t want to diminish his ego and accepts what he has given her in order to keep him happy. Her love for her father goes so deep that she cannot hurt his feelings. After all, it seems that he’s given her so much that she doesn’t want to seem like an ingrate daughter.

In the modern era of Only Yesterday, Taeko holds her own dream and head full of ambitions. When a talent agent seeks Taeko for a college production, she’s filled with grandiose fantasies of stardom and magazine shoots. All this shatters when her father declares that Taeko cannot perform in the play, offering only a vague rationale: “Show business people are no good.”

Although it may have been reasonable for Taeko’s father to keep Taeko’s visions of grandeur in proportion, he doesn’t make reasonable attempts to explain his rationale to Taeko, leaving her in the dark about why she can’t pursue her desires. Taeko’s female family members attempt to change his mind, but in Japanese society, the father has the final word on the decision-making, despite the protest from a female-majority family unit.

For Taeko, time almost compensates for these childhood woes when adulthood grants her the space to subvert tradition away from her parents’ domain. She mentions that she sampled theatre club in her later years, though quit on her own terms.

In addition, Taeko retains a black sheep status within her family, avoiding the feminine convention of desiring a husband. Her singlehood at age 27 is seen as an affront to her mother and her culture, despite her having a relatively comfortable autonomous life in her own apartment. Taeko acting on unconventional desires is a triumph of sorts, though she still has to grapple with feminine standards in Japan, such as a clerk who micro-aggressively assumes she broke up with a boyfriend when she clocks-in her vacation time.

Kaguya’s society also expects her to be bound to a male significant other. Unlike Taeko’s modern situation, though, where Taeko has an easier time saying “no” to marriage, Kaguya is chained to the protocol of her time period in ancient Japan. Kaguya roots herself in the rigidity of tradition, suppressing her wild spirit to adapt to the princess mantle, while the men in Kaguya’s world exercise the freedom to be bumbling and solicitous.

Kaguya remains anchored in the confined spaces constructed by her father, poised behind bamboo blinds or the box of her banquet tent, which locks her away from being present at her own banquet. Despite initial resistance, she accepts noble appearances, having her teeth blackened and brows plucked away.

Takahata lampoons the double-standard of propriety by depicting Kaguya’s suitors as men who stumble and shove each other, breaking their noble grace with antics of buffoonery, when approaching and wooing Kaguya. In spite of noble protocols, men break them frequently with no consequences. Kaguya’s father also trips over himself, but he and the noblemen have no repercussions for their gracelessness.

Meanwhile, Kaguya’s stern teacher imposes demands on Kaguya’s conduct and appearance for the vision of perfectionist womanhood. There is less pressure for princes and Emperors than there is for a princess. Takahata reprimands the deep pretense of patriarchy by illustrating men who condone their own transgressions while shaming a daughter like Kaguya into silence.

As a prisoner to palace protocol, Kaguya does not defeat the gender boundaries enabled by her father, but she does find ways to operate within them. The line-up of suitors plead for her hand, intent on winning her as a trophy wife, even disposing of their previous marriages to make space to possess Kaguya as their new vase.

The princess plays to the male ego of her suitors by pretending to be attainable rather than outright reject marriage in front of her father. She can’t turn her suitors away, but she can question if they measure up. She has no power to order her father to cancel courtships, but she can delay courtships or play with the boundaries. She toys with masculine pride by subjecting her suitors to trials for impossible and legendary treasures to win her hand.

Although it offers her amusement and some empowerment, her suitors’ endless quests gradually poison her mental state, as she comes to terms with the incessant objectification of her body. In one cruel scene, a suitor nearly wins Kaguya’s heart not by offering treasure but by proposing that they live in the countryside, playing to her thirst for freedom, only to discover that he had disingenuously recited the same vow to his previous wife.

Kaguya knows that she is nothing but a game to powerful men. When Kaguya finally exercises some explicit power over her father, she threatens suicide, as if to tell him that if he loses her than she will no longer be his possession—though such a last-resort act of agency would also rob her of her life.

It’s telling that Takahata, an animator of natural vistas that have been a staple in Ghibli films, has Kaguya and Taeko seek refuge in nature far from the supervision of fathers and patriarchal constraints. In saffron-saturated fields, Only Yesterday‘s Taeko finds refuge from the confinement of city life, which gives her the space to reflect on the social constraints that haunted her decisions, particularly the decisions of her father.

Similarly, Kaguya’s childhood peasant life in nature does not tether her to standards as much as palace life does, where restrictions are fully defined. In the fields, Kaguya’s emotions can soar. She laughs in rapture and runs barefoot across the fields without expecting scolding as she sheds her princess pretenses. But at the end of the day, Kaguya is obligated to return morosely to the mansion walls of her father.

Both Kaguya and Taeko remain haunted by the what-could-have-beens if gender barriers hadn’t obstructed their dreams. After a violating touch from the Emperor who her father welcomed into her space, Kaguya has enough of the objectification. In an attempt to regain autonomy over her body, she unknowingly calls to the moon delegates to take her away.

The unhappy princess returns to the moon, escaping the social constructs that festered her unhappiness, but she pays a dear price: The memories of her parents and her passion for the countryside.

Only when it’s too late does Kaguya’s father realize his own patriarchal obsessions drove his daughter to despair. Had Kaguya’s father not been oblivious to her evident pain and so presumptuous of her welfare, perhaps Kaguya would have lived happily in an earthly life with the parents and “birds, bugs, bees” she loved, away from the greed of men seeking to make a wife out of her.

Living in a modern age, it takes years for Taeko’s agency in Only Yesterday to formulate enough for her to break from her mold. When the adult Taeko stays on the farm rather than return to her office cubicle, it does not absolve the ills and missed opportunities of her past, but her decision unfurls new possibilities.

She has no pretenses that the change won’t be challenging, knowing that she will have to adapt to the harsh weather of farm life. But she is walking her own path on her own terms without her father’s judgment.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya has a rather cautionary message for societies that perpetuate patriarchal trappings for their daughters. As much as she might fight, the damage on Kaguya was irreversible. On the other hand, the modern setting of Only Yesterday allows breathing space for the female protagonist to work toward a happier ending.

However, Tahakata also suggests that happiness should not be a concept that woman have to earn and strive for. They should have been offered more freedom to explore and attain their desires. Both Kaguya and Taeko undergo mental and societal labor to assuage the effects of patriarchal order in their lives.

The solution would be to dismantle and interrogate the laws and customs in place. Through the tribulations of Kaguya and Taeko, Takahata shows that girlhood and womanhood deserved better in the male-dominated societies that raised them.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.